(Bloomberg) -- Singapore’s main stock index is on track to have its best annual performance since 2017, but any celebrations over the Straits Times Index’s 15% gain so far this year are likely to be overshadowed by doubts about what lies ahead.

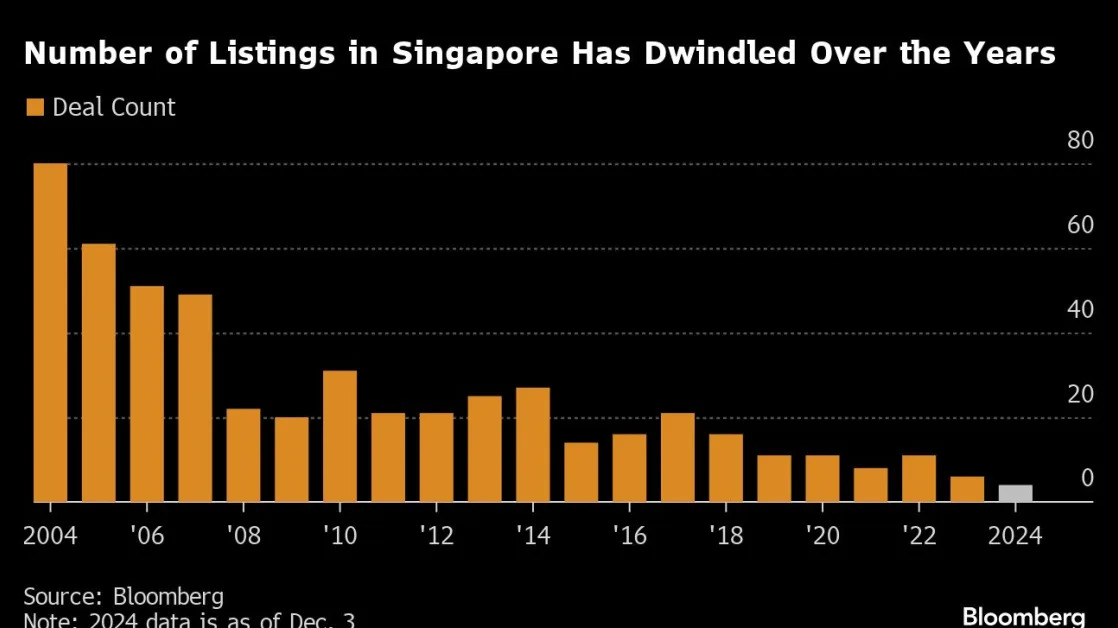

Even with the index hovering near its record high for weeks, investors say the bourse is a shadow of its former self, with delistings outnumbering new listings, the membership less diverse and prominent regional companies such as Grab Holdings Ltd. and Sea Ltd. going public elsewhere.

For traders who have lived through the boom-and-bust cycle of Singapore stocks, there’s a stark difference between the euphoria back on that record day in 2007 and the reality now.

“In 2007 we saw loads of liquidity. Basically everybody was talking about stocks,” said Terence Wong, chief executive officer at Azure Capital Pte., an investment firm he founded in 2015 after more than a decade on the sell-side. Now, “the Singapore market is just one of the many options that investors have. It is in a very sad state.”

Maybank Securities Pte.’s Thilan Wickramasinghe, who has worked through both stock market peaks, echoed those sentiments.

“There were a lot more listings coming in, a lot more capital,” said Wickramasinghe, who joined the brokerage industry two decades ago. “You could see the changes in Singapore almost on a monthly basis.”

A deeper look at the STI’s gains this year suggests the rally is primarily driven by banks — with the trio of DBS Group Holdings Ltd., Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp. Ltd. and United Overseas Bank Ltd. making up more than half of the benchmark’s weighting. That compares with less than 30% in early 2008 when the index was revamped to its current 30-member composition.

Another difference is the liquidity. Daily traded volumes in the city-state are far lower than other regional markets such as Australia and Thailand, Morgan Stanley analysts including Nick Lord wrote in a recent note. Nearly 90% of daily trades in Singapore can be attributed to just 30 of the largest stocks out of more than 600 listed firms on Singapore Exchange Ltd., and most of these volumes are less than $10 million a day.

Retail investors make up just 15% of the total turnover in Singapore, compared with 35% in India and 87% in China, according to a UBS Group AG report earlier this year.

Chinese ‘S-Chips’

“I don’t think we are anywhere near the level of market buzz we saw in 2007,” said Paul Chew, head of research at brokerage Phillip Securities Pte.

At the time, a wave of Chinese companies known as S-chips were listing on the SGX, generating excitement among local investors.

“This time around, there isn’t any strong thematic around the mid-caps,” said Chew. “How long can we sustain the rally with just the banks?”

Singapore officials acknowledge that things could be better.

“Everyone can see there is a need for us to do something to improve the situation that we face today in Singapore,” Second Minister for Finance Chee Hong Tat said in August.

The global financial crisis wasn’t the only catalyst for the collapse and subsequent stagnation in Singapore stocks. The Chinese “S-chips,” which generated such enthusiasm ahead of the 2007 record, were also part of a series of high-profile scandals in the 2010s that caused Singapore authorities to tighten market regulation. A penny-stock crash in 2013 further contributed to a loss of retail confidence.

Now Chee is leading a newly formed task force assigned with creating an action plan to revive the market by next summer. The committee will consider “initiatives to improve the vibrancy” of the stock market, and study ways “to galvanize greater private sector participation” in the effort, the city-state’s financial regulator said in August.

Participants on the task force include state investment firm Temasek Holdings Pte. The move follows similar initiatives in Japan and South Korea and — if it works — could drive up valuations and boost stock trading liquidity, according to analysts.

Family Offices

The group has been discussing setting up a fund backed by billions to invest in Singapore stocks, though the exact structure hasn’t been pinned down. One potential model is Thailand’s state-controlled Vayupak Fund, which offers a guaranteed annual return, has external fund managers and a heavy equities bias, according to people familiar with the matter.

Other ideas include persuading local companies or those who have benefited from the stable rule of law in Singapore to list locally, either via secondary or primary listings, the people said, who asked not to be identified discussing private matters. Family offices may also be asked to boost their investment threshold in local equities, according to the people.

In its report, Morgan Stanley said that “Singapore already possesses many of the ingredients needed” to bolster the market. One idea, it said, is to make greater use of the city-state’s mandatory social security fund, known as CPF, which it said is “under-allocated to domestic equities.”

With the task force’s deadline still months away, discussions are still in an early stage, the people said.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore said many ideas have been floated and “discussions are still ongoing, to determine which ideas are feasible and impactful.” The review group will share more when ready, it added.

‘Quite Successful’

To be sure, the market’s woes don’t overshadow Singapore’s successes in other aspects. Since 2007, the city-state has continued to cement its position as a leading financial hub, competing for tech and talent with cities including Hong Kong and Dubai. Its efficient public transport, high quality of life and stable politics are the envy of the region.

“Singapore is already quite successful without a very large local stock market,” said Hugh Chung, chief investment advisory officer at Endowus, a digital wealth platform. “Our clients have done well because they have global exposure. So the local market limitation is not necessarily a huge threat, in my view, for the wellbeing of Singaporeans.”

The country has a track record of reinventing its stock market. Over the past two decades, it has become a global listing hub for real estate investment trusts thanks to its favorable tax regime and well-established legal system.

“When we have embraced change, like in adapting our markets for REITs, we have done very well and continue to be a leader in these listings,” said Stefanie Yuen Thio, joint managing partner at TSMP Law Corp. “Political will is what makes the difference.”

But some local players also see missed opportunities. Strict Covid restrictions in China and Beijing’s tightening grip over Hong Kong sparked a migration of family offices to Singapore, but that shift didn’t translate into increasing investment in the local equities market.

That alone should be cause for concern, said Maybank’s Wickramasinghe.

“Whether you like it or not, the strength of the equities market is the most public and transparent way the world can judge how successful a financial center is,” he said. “You can’t call yourself a global financial center without having a thriving equities market.”

--With assistance from Joyce Koh and Andrea Tan.