(Bloomberg) -- Australia’s monetary policy effect is no more potent than those of other advanced economies, even though its households carry a large stock of variable-rate mortgage debt, a senior Reserve Bank official said.

Assistant Governor Christopher Kent said Monday that the central estimates from RBA models of how much GDP and inflation decline in response to an unanticipated increase in policy rates sit near estimates generated by models in the US, euro area, UK, Canada and Sweden.

“This outcome reflects several features of the Australian mortgage market that collectively leave most borrowers with buffers that help them to manage through a period of higher interest rates,” Kent said in the text of a speech at the Australian National University in Canberra.

“That has been the case through the recent episode, although many borrowers have struggled in the face of rising interest rates over the past two years or so, and household spending more broadly has weakened noticeably.”

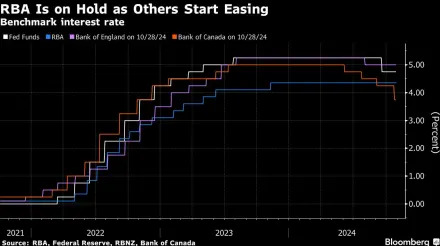

Australia’s households are among the world’s most heavily indebted as property prices defied gravity in recent years, particularly in the bellwether Sydney market. The RBA joined global counterparts in tightening in 2022 to counter surging inflation, though it opted not to raise as much as many central banks in an effort to shield the labor market.

The RBA’s cash rate sits at a 13-year high of 4.35% and was about 1 percentage point below the peak rates in the US and New Zealand. One argument from economists for this difference had been that the rapid flow-through of hikes to floating-rate mortgages was likely to restrain Australian households from spending. Yet Kent said this wasn’t really the case.

He said one way to judge the “overall potency” of policy is to compare its effects across different economies on aggregates like GDP and inflation using macroeconomic models.

“Doing so for a range of models for several advanced economies suggests that the effect of monetary policy is neither faster nor more potent in Australia than elsewhere,” he said.

Kent touched on forward guidance, noting that outside of the pandemic, the RBA has tended to provide it less frequently, in less explicit and more qualitative ways, and covering shorter terms than some other central banks.

He pointed to a number of suggested reasons for Australia’s approach, including one from former Deputy Governor Guy Debelle, who argued that if the reaction function “is sufficiently clear, then forward guidance does not obviously have any large additional benefit and runs the risk of just adding noise or sowing confusion.”

Kent said he thought it would be worth reviewing the RBA’s approach to forward guidance from time to time. This would include considering “other ways that the RBA might clarify the nature of its reaction function,” he said.