(Bloomberg) -- US President Donald Trump’s plan to revoke Chevron Corp.’s operating license in Venezuela threatens to force the nation’s oil sector back into the shadows, paving the way for corruption and huge discounts in the Asian market.

The presence of the Houston-based oil giant brought much-needed transparency to Venezuela after a period of sanctions imposed during Trump’s first term. In those days, the country relied on ghost cargoes and small traders, resulting in billions of dollars of lost revenue for state-run Petroleos de Venezuela SA between 2020 and 2022.

Widespread graft and an ensuing power struggle led President Nicolás Maduro to purge one of his top allies, Tareck El Aissami, with the former energy minister now behind bars in Caracas. Analysts and economists warned that without Chevron as an active participant, Venezuela’s crude sector is headed back to something similar since all the nation’s oil revenue would flow through PDVSA.

“If the US and Western energy companies pull out of Venezuela, Maduro will increasingly be forced to rely on shady intermediaries to ship its oil,” said Geoff Ramsey, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

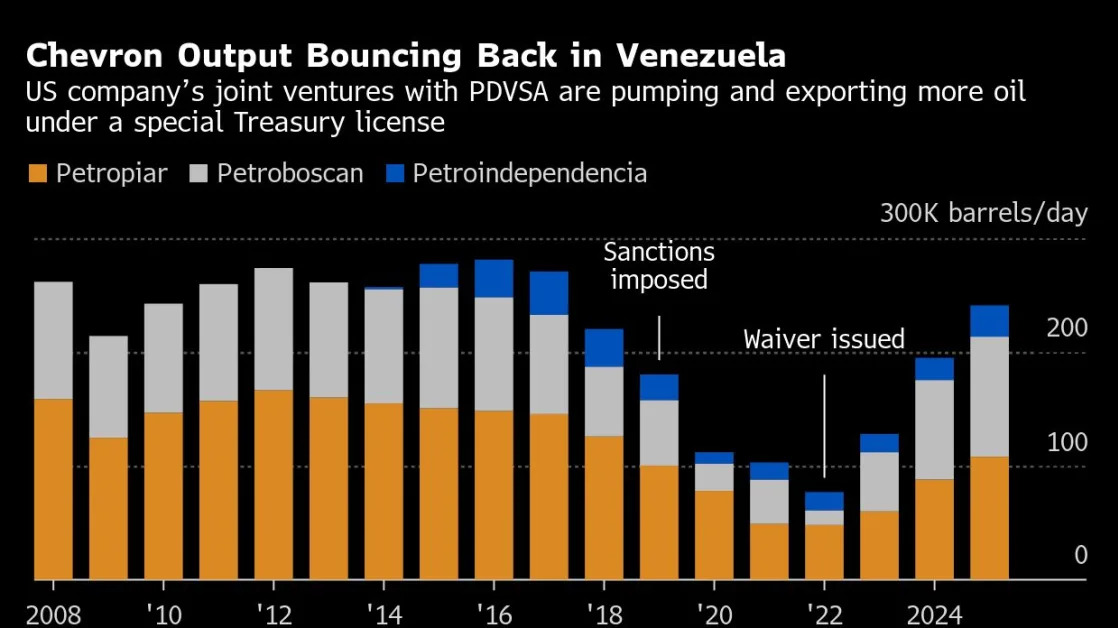

Trump declared Wednesday that he plans to scrap the waiver that put Chevron on track to ramp up exports from Venezuela to a seven-year high this month. His pronouncement also raises questions about the other oil majors the US government has allowed to keep producing Venezuelan crude, including Repsol SA of Spain and France’s Maurel & Prom.

Should Trump follow through on his threat and cancel the Chevron license, he would deliver a harsh blow to Venezuela’s incipient economic recovery — potentially fueling more of the irregular migration into the US his government is trying to halt. And in addition to reducing corruption, Chevron’s increased oversight has also helped alleviate the country’s perennial fuel crisis since it could ship its own diluent from the US instead of relying on PDVSA’s dwindling production.

Chevron is “aware of the president’s announcement” and is “considering its implications,” spokesperson Bill Turenne said by email. The company “conducts its business in Venezuela in compliance with all laws and regulations, including the sanctions framework provided by US government.”

After Trump imposed oil sanctions in 2019, Maduro’s regime attempted to circumvent the ban by renaming tankers and using ghost vessels that switched off their transponders to sail without being detected by the US government. Many shipments, which were assigned to intermediaries close to government officials, neither reached their final destinations nor resulted in payments to PDVSA accounts.

More than 50 others were locked up along with El Aissami, including judges, elected officials and the head of the Andean nation’s crypto regulator. Pedro Tellechea, who took over as oil minister between 2023 and 2024, was also arrested last year after being accused of handing over sensitive PDVSA information to an entity controlled by US intelligence.

In an effort to control the fallout, Maduro tapped Vice President Delcy Rodríguez to take charge of the energy ministry and keep close tabs on PDVSA’s board and all its commercial trading operations.

Should Chevron withdraw from Venezuela in six months time, when its license would expire barring a reversal from Trump, PDVSA would likely be forced to reroute sales to Asia from US refineries at prices discounted by about 20%. That would reduce national revenue by as much $3 billion, according to Síntesis Financiera, a Caracas-based analysis firm.

“In the medium term this will affect the sustainability of total production,” she said.