U.S. stocks tumbled on Friday after a blockbuster December jobs report .

At first blush, to some investors, that reaction might seem surprising. The labor market is expanding at its fastest pace since March, with job gains seen across a broader swath of industries. And the resilience of the U.S. economy and labor market had received much of the credit for powering the U.S. stock market over the past two years. So what changed?

The blame seems to lie with rising Treasury yields. They have been gaining rapidly even as the Federal Reserve has sought to lower short-term interest rates since September. Apollo Global Management Chief Economist Torsten Slok recently characterized this pattern as extremely unusual.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury note BX:TMUBMUSD10Y, seen as the benchmark for the U.S. bond market, gained nearly 80 basis points during the fourth quarter, rising at the fastest pace since the third quarter of 2022. It has continued to climb in January. On Friday, it moved as high as 4.79%, a level it hadn’t seen since late 2023.

A number of factors have contributed to the increase in yields. Some have blamed “bond vigilantes” — a term used to described investors who sell bonds to protest a government’s profligate fiscal policies. Others have blamed fears that a strong economy could help rekindle inflation. It was this last factor that appeared to be in focus on Friday.

Live coverage: The 30-year Treasury yield tapped the 5% mark after blockbuster U.S. jobs report

Adding to the downbeat picture is the fact that, recently, rates have been rising in Europe and Japan. Seemingly, China is the only major economy where bond yields have remained anchored.

These fears have contributed to a dynamic known on Wall Street as “good news is bad news” — that is, good news for the economy and labor market is treated as bad news by the stock market. The upshot is that investors want to see a strong economy but not so strong that it causes inflation to pick back up, forcing the Federal Reserve to start raising interest rates again.

The S&P 500 SPX sank in December as yields pushed higher. Losses have continued in January, and the index was down nearly 1% on the month as of Friday’s close, with Friday’s decline wiping out gains from the start of the year.

The Nasdaq Composite COMP and Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA also tallied their biggest declines since Dec. 18, the day when the Fed delivered its most recent interest-rate cut.

According to the latest data, U.S. GDP has continued to grow at an above-average pace. Despite this, pockets of weakness have persisted, exacerbating investors’ fears that interest rates could remain higher for longer.

The housing market has struggled with mortgage rates north of 7%. Commercial real-estate borrowers have managed to term out debt — hoping that rates will fall, sparing the market from a full-blown meltdown. But it’s unclear how long these companies can hold out; the longer rates stay elevated, the greater the risk.

Manufacturing activity, which is also extremely interest-rate sensitive, has continued to struggle, as have lower-income consumers.

According to the latest Federal Reserve data, delinquency rates on credit cards have climbed to the highest level in nearly 15 years. Shares of companies like Dollar Tree Inc. DLTR and others that cater to budget-conscious consumers have tumbled.

Investors are concerned that, if borrowing costs don’t fall and inflation rebounds, even wealthier consumers could start to struggle, causing corporate profit margins to shrink.

“The market is worried about the potential for continued heightened interest rates impacting companies and consumers and the potential for growth to restoke inflation in the future,” said Brent Schutte, chief investment officer at Northwestern Mutual Wealth Management Co., during an interview with MarketWatch.

“There’s also the fear that, at some point in the future, the Fed might have to hike rates again, which has raised the possibility of slower economic growth in the future.”

Futures traders pared back their expectations for how many interest-rate cuts the Fed will deliver in 2025 after Friday’s jobs data. The latest figures from CME Group show that one cut between now and December is seen as the most likely scenario. The Fed’s target range for its policy rate stands at 4.25% to 4.50% after a 25-basis-point cut in December.

Adding to investors’ anxieties, a team of economists at Bank of America said that they didn’t foresee the Fed cutting interest rates at all in 2025. While it isn’t the B. of A. economists’ base case, they now see a rate hike as more likely.

Inflation has eased sharply from its peak in the summer of 2022. But the pace of its decline has more or less ground to a halt over the past few months, leaving the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge above the central bank’s 2% target.

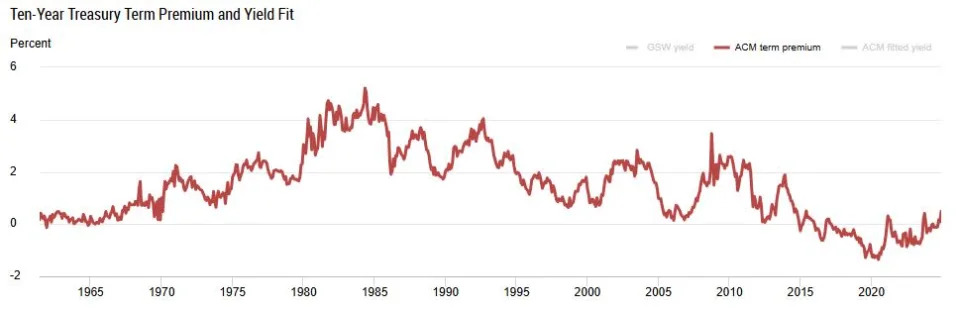

In response, investors have dialed up their expectations for how high inflation might remain over the next few years. This is reflected in markets via something known as the term premium.

Derived from a statistical model developed by three Fed economists, Tobias Adrian, Richard Crump and Emanuel Moench, the term premium is intended to explain how much additional yield bond investors are demanding to compensate them for the risk that interest rates might change over the life of their investment.

As of the end of December, the 10-year term premium stood at just under 0.5%, its highest level since 2014, Federal Reserve data showed.

Inflation is a big part of what’s driving the term premium higher. But concerns about unchecked federal spending are also a factor, said George Cipolloni, a portfolio manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management.

“People are focusing on the term premium now, and it’s telling you that they want more yield to take that risk,” Cipolloni told MarketWatch on Friday.

The impact of all of this has been amplified by the fact that stock-market valuations are high relative to historical norms, Cipolloni said.

President-elect Donald Trump’s policy agenda also has contributed to investor unease when it comes to the stock market, said Robert Conzo, chief executive officer at the Wealth Alliance. Trump’s promised tariffs could help revive inflation, while his plans for more tax cuts could cause the federal budget deficit to expand, adding more upward pressure on bond yields.

“The tone is one of a lot of uncertainty,” said Conzo, even coming off two straight years of more than 20% gains for the stock market.

“It seems as if the general investor just doesn’t believe that markets are good, or will be good in the future. There’s just a very pessimistic tone,” Conzo said in an interview Friday with MarketWatch.

While the stock-market rally has suffered a setback recently, the S&P 500 is up more than 60% since its bear-market low on Oct. 12, 2022, FactSet data showed.

There are still plenty of reasons for investors to remain bullish. Corporate earnings growth is expected to be strong this year, which could help justify stocks’ lofty valuations. Although the bar for another year of double-digit gains is high, the fact remains that momentum remains on investors’ side, Cipolloni said.

The degree to which stocks can climb moving forward will likely depend on whether bond yields continue higher. Investors could face another challenge next week when December’s consumer-price index, a popular inflation gauge, is released. But the fourth-quarter corporate earnings season is also kicking off.

According to FactSet’s John Butters, S&P 500 companies are expected to report their strongest earnings growth in three years. That could be enough of a distraction from inflation and interest rates to send stocks higher once again, Cipolloni said.

Joy Wiltermuth contributed.